Watch

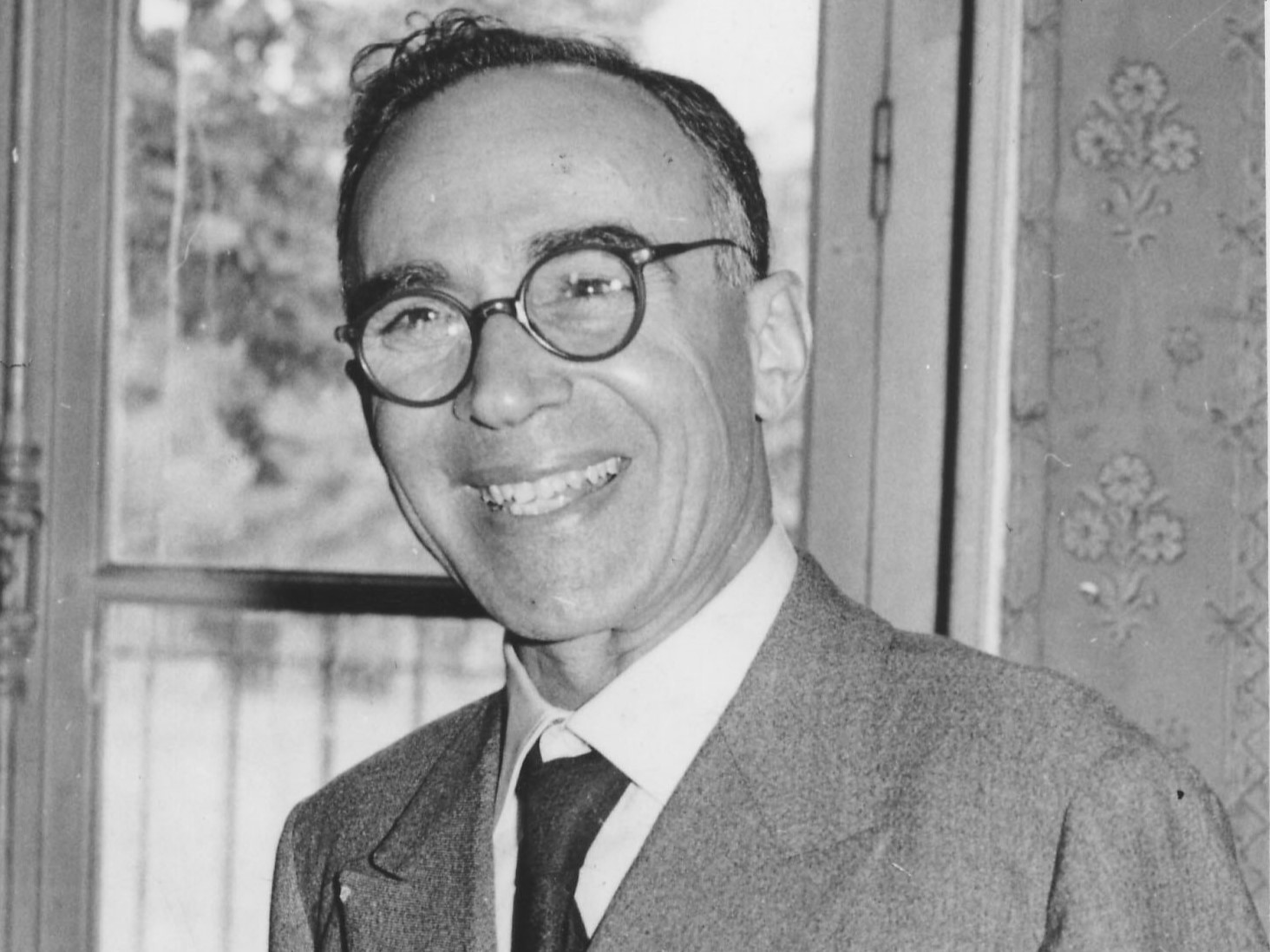

Giorgio la Pira: the ‘Poor Among the Poor’ Mayor of Florence

Giorgio La Pira was a different politician, a believer, a man who experienced poverty with the poor, and a person convinced that politics could be a form of charity. Looking back on Giorgio La Pira’s life and legacy with us is Maurizio Certini, vice president of the foundation carrying his name.

Giorgio La Pira was a politician, and a man of great depth. Professor of Roman Law, he was also a member of the Constituent Assembly that wrote the Italian Constitution, three times the Mayor of Florence, and a deputy. For the values he embodied throughout his life, for his actions, he can still today be considered a beacon for younger generations.

This is why we are trying to paint a picture of Giorgio La Pira, with the help of Maurizio Certini, vice president of the La Pira Foundation, in Florence.

How much did Giorgio La Pira devote to his vulnerable neighbours?

The poor were at the centre of his life. Florence’s impoverished were his family, because he experienced poverty with them. La Pira chooses radical poverty, similar to St Francis. He always shares what he has, because he considers poverty an evangelical quality, if chosen freely. He considers the Gospel a book of the poor and a text on human sociality, but it will continue to be a touchstone in his political life. He sees in the poor another Christ, and – in the pathology of our current economic system – he recognises the great responsibility of alleviating poverty, and intervenes, working in politics for love.

La Pira was a religious convert at twenty years old…

There are, in fact, many beautiful writings by 20-year-old La Pira, from Easter of 1924. They are the words of a young man in love, of an ‘explorer of paradise’ – as Dossetti, a friend of his at the Constituent, describes him – who will liken this intense, mystic experience of his to that of Francis of Assisi in San Damiano. With the support of his teacher, specially his literature’s teacher, He meets, as he himself says, ‘Jesus, the Master’ and follows him in a radical way throughout his life of study, of teaching, as a mayor who experienced poverty with the poor.

What was La Pira’s life like before that?

He is born in 1904 in Pozzallo, a small fishing village in the south of Sicily; he is raised in Messina, in an anticlerical setting; he is influenced by Marinetti’s futurism. But, even in this context, he does not lack social awareness, which is demonstrated by the care he shows for the people living in emergency housing on the outskirts of Messina, after the 1908 earthquake. La Pira helps them, plays with their children.

What happens when he reaches Florence?

He arrives in 1926 as a student, having been called upon by his professor, the eminent Romanist Emilio Betti. Here La Pira writes his dissertation and develops a strong attachment to Florence, teaching at the university and devoting himself to serving the poor with the St Vincent de Paul society. After a brief period as the undersecretary for labour, he will become mayor – from 1951 to 1965. He will give a new face to this war-torn city, keeping five issues close to his heart: work, housing, healthcare, education, and a space to pray for all.

What is his path to politics?

He studies the philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas in depth, and embraces its political dimensions, always keeping humans at heart, along with the dignity of every man and every woman, putting the latter first. Following the teachings of his friend Pope Paul VI, he restores politics as the highest form of charity. In 1934, he founds the ‘Mass for the poor’ – still held in Florence today – which views the Eucharist as the pinnacle, the centre of connection. He founds the Community of San Procolo, which brings together the poor, the rich, and the young. There is nothing paternalistic about La Pira’s approach, because La Pira experiences poverty with the poor. On Sundays he will always be with the poor, helping them, informing them about political and international issues. In exchange, he asks for their prayer, convinced that everyone has something to give.

How does his story unfold during fascism?

In 1938 the Italian racial laws are passed. It is established that some citizens are no longer so. They no longer have the same rights as others. A friend and colleague of La Pira, Professor Cammeo, is forced out of the university for being Jewish.

How does La Pira react?

He does not take up arms, but writes. In January 1939, he begins a new supplement in the Dominicans of San Marco journal Vita cristiana: a monthly publication that does not lay blame, but which strongly opposes the doctrine and practices of fascism. He calls it Principles.

What is written in Principles?

It gathers writings from classical antiquity together with pages from the Bible and from the fathers of the Church. It talks of the importance of humanity: human dignity, freedom, equality, solidarity, justice, and peace as an end goal for humanity. It talks of work and social rights, and the role of the state as their guarantor. It exposes the immorality of war. Following Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, it published a very harsh article in its September 1939 issue. The magazine continued until 1940. when it would be suppressed by the fascists.

What happens next?

La Pira was controlled by the Fascists, but nevertheless continued to travel and speak in many places until he was forced to go into hiding and then flee to Rome, where he stayed with Monsignor Montini (the future Pope Paul VI). In Rome, he met other intellectuals who had taken refuge in the capital, such as Calamandrei. He also met Igino Giordani, with whom he developed a special rapport. In 1945, he published one of his most important works: La nostra vocazione sociale (Our Social Vocation).

What becomes of Principles?

It remains an exceptional cultural work, because the principles of our Constitution can be found throughout that publication.

After the war is over does La Pira go back to Florence?

He returns much earlier. La Pira is anxious. He returns as soon as the Allies allow him to pass, because Florence has been liberated and the war continues, slowly moving towards northern Italy. It is 2 September 1944. He is given roles that centre around caring for the poor, since he knows them all. He is nominated President of the ECA, or Ente Comunale Assistenza (Municipal Assistance Authority). At the same time he is becoming part of the Assembly working to draft the new Constitution, in which he will play a key role in writing the Fundamental Principles.

Those principles that keep coming back…

Article two is written entirely by La Pira, as well as part of article one. Articles three to 11 deal with Italy renouncing war as a tool for resolving international disputes. La Pira was already prepared.

Intense years…

One day in Rome, working on the Constitution, the next in Florence, serving the poor.

Theory and practice, words and actions

In the essay Our Social Vocation, he writes: ‘Our internal lives are not enough. Our lives must be constructed on external channels that enable us to move in the company of man. We must transform society. We must walk with Jesus through the streets of the world.’

Does La Pira always marry spirituality with politics?

He brings all this to his experience as the undersecretary for labour in the first De Gasperi government. Here he comes face to face with unemployment, and decides to study it. In 1950 he publishes L’attesa della povera gente (The Wait of the Poor), where he sets out his economic vision. This serves as a precursor to the uncompromising and forward-thinking decisions he will make in Florence as the mayor, in defence of the right to work – which he felt could not be crushed by the system of profit that only favours a small few. La Pira is clear about article one of the Constitution: ‘Italy is a democratic Republic founded on labour’. But he does not stop at good municipal administration. He changes what the mayor does politically, promoting Florence on an international level as a peaceful place by twinning cities, using the slogan ‘uniting cities to unite the world’ at very important international conventions for intra-Mediterranean dialogue. He viewed the Mediterranean as a sea that united brotherly peoples – Jewish people, Muslims, Christians – through actions of peace by both the East and West, by supporting ‘new populations’ emerging from colonial regimes, and by writing disarmament proposals. In the middle of the Cold War, he creates space for diplomacy. He paves the way for significant negotiations and international agreements. His connection with the greats of this world is immense. His letters to the popes serve as a precursor to new teachings that would become part of the Second Vatican Council.

How do Christianity and peace feature in La Pira’s life?

His Christianity is deeply rooted in a faith that sees God’s ongoing actions for the good of the world. Through this, he understands the ultimate meaning of History, whose path points towards the mouth, as a river does with its bends, its paths back left behind. He moves towards the sea, the embodiment of peace. His is not an ideological faith; it is concrete, forward-thinking. It is the faith of a free man, moved by a spiritual moment from which all ties with power have been cut.

Not his ties with the poor…

Returning to Our Social Vocation, La Pira writes: ‘I cannot be indifferent to the fact that my brothers are forced to live in an economic regime that is at odds with their nature as human beings. In a legal or political regime that violates their fundamental human rights.’

The poor as brothers…

Fraternity is a big part of La Pira’s life, a man who used to be a Dominican tertiary and Franciscan. He associates it closely to Pope Francis.

Could we say that La Pira brings many wonderful things to politics?

On politics, he writes: ‘My vocation is singular and structural. I have never wanted to be mayor, nor deputy or undersecretary. But never let that ignorant cliché be said that politics is a nasty business. Political engagement, in a society that has been constructed on Christian principles, is – in all its systems, starting with its economic system – a commitment to humanity and holiness.’

What is another key word for La Pira, one that is still pertinent today?

La Pira is known as the ‘Prophet of Hope’. He would often invoke the Pauline expression ‘spes contra spem’ (hope against hope), and was also clear on his belief in St Augustine’s definition of hope as a virtue with two daughters: anger, with the way things are, and courage, to change them. La Pira prayed, studied the real world, and intervened, always working to bring people together.

How important is it that young people today know about Giorgio La Pira?

La Pira is a hugely important figure. His impact was far-reaching, and his philosophy touched on a variety of disciplines. He has a lot to say to our generation, and future generations alike. You only need to read his writings to understand how applicable they are today. As a man of the twentieth century, perhaps his language can seem dated, but La Pira always spoke directly to the heart and the mind. He knew how to talk to young people. During the unrest of 1968 he was one of the few professors that the students would listen to, because he would offer them perspective and, like them, he knew to look ahead. La Pira dreamed with the young people, and his ability to grab hold of a dream captivates them even now. His entire philosophy is very topical. La Pira was both a dreamer and a realist. He emphasises that peace is worthwhile. And that war, having entered the atomic age, has become ‘impossible’, because after Hiroshima, humanity risks self-destruction. In his book The Path of Isaiah, a collection of writings and speeches from 1965 to 1977, republished with a preface by Mikhail Gorbachev, he clearly explains how the only possible path to peace is through politics, global negotiation and disarmament, starting with nuclear weapons. After his term as mayor ended in 1965, as president of the World Federation of United Cities, he committed himself rigorously to the construction of peace, until his Sabato senza vespri (Saturday without Vespers) on 5 November 1977.

www.centrointernazionalelapira.it

Article translated into English by Becca Webley