Watch

Empathy and fear, the present and human nature: interview with director Cristian Mungiu | Part 2

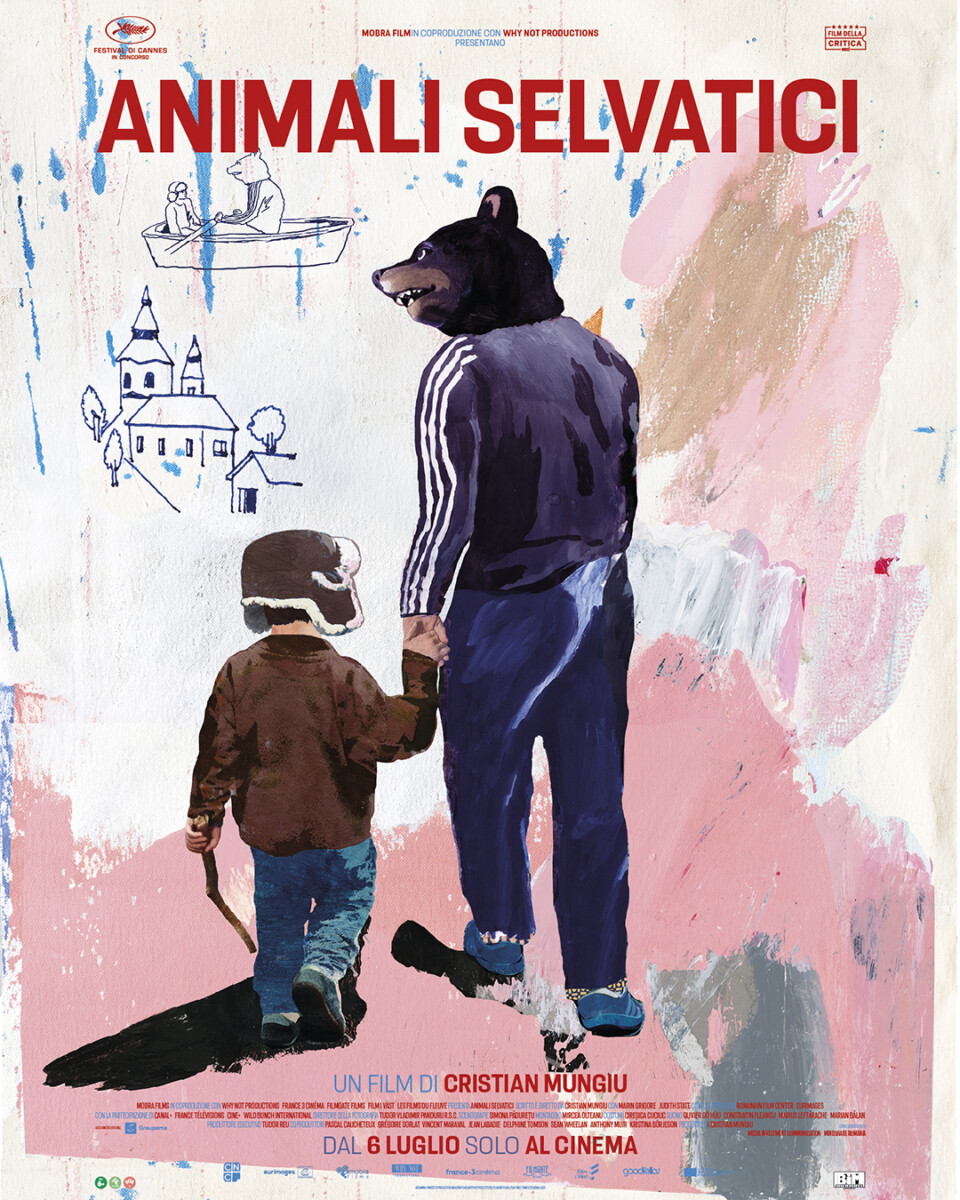

“R.M.N” (“Wild Animals”), his last film, is set in a small country of Transylvania, where the balance of the local community (made up of different ethnic groups) is put to the test by the arrival of some Sri-Lankan workers. The film reflects on the present and the on the human nature, problematically touching on the themes of the other, of encounter, of violence and love, of acceptance. We talked about all of this with director Cristian Mungiu, winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes (2007) with ‘4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days’, and Best Director, also at Cannes (2016), with ‘A Father, a daughter’. Here is the second part of the interview (click here to read the first part):

Another important character of the film is Matthias, the male protagonist of R.M.N. He seems to be a man (at least in the beginning) stuck in a middle ground: he is suspended between leaving his hometown (we find him emigrating to Germany) and a melancholic return home, after having suffered an episode of racism. He is also suspended between two women: his wife with whom he is separated, and Csilla, with whom he had a love affair but who now rejects him. He has an elderly father, who is about to leave, and a son to raise, whom he teaches to hunt and defend himself against the wild animals. But it seems to me that slowly even Matthias, not too differently from Csilla, becomes aware that the closed, wild, violent mentality that surrounds him takes him nowhere. It is as though within his stillness exists a silent inner mobility. Is that so or am I wrong?

For Matthias, the rhythm of the changes of this world is too fast and this brings him a lot of anxiety as he cannot decide for what kind of world he needs to prepare his child. The values he has learnt from his father are of no use today while his need for affection is as significant as any other’s human being. He is indeed not a typical main character (as you can see in mainstream cinema where everything is clear and the main character is a different person at the end than at the beginning), he is doubtful from the beginning to the ending but still, as you observed, there is change in him. On one side, he learns a difficult lesson when being abandoned by the women he loves: that even if you don’t want to get involved socially and prefer to conform and to focus on your own problems, your responsibility exists – and you need to make choices as you might be considered guilty even if you chose not to act. The second thing he becomes aware of – by the end of the film is that we, as humans, have this dual nature: in part humans capable of empathy, generosity, and tolerance and in part animals, basing our survival on violent instincts, on suspicion and on selfishness. At the end he finds himself in between these two worlds – the darkness of the forest and the warmth of the community and he understands that he needs to make a choice – but most importantly is for us to understand in our real lives that we need to make this choice – if not, in any unexpected situation, (like an accident or a war) the animal in us will prevail.

There’s a long sequence shot in R.M.N in which the villagers gather to discuss the issue regarding the hiring of the Sri Lankan workers in the bakery. Csilla is also present and uncomfortable phrases on integration are let out. Words and thoughts that unfortunately we have heard many times around. The film doesn’t judge, but photographs, x – rays as the title R.M.N says. It can be interpreted as a pessimistic film, but also as a mirror through which we all can better see our own sterile and dangerous capacity to close ourselves off and close our doors to our fragile neighbors. Here, however, art returns to provide us with that little shock that sets in motion or fuels change, growth. Does this seem like a good way to read your film?

I am very happy that you see it this way. Art is a mirror but often people hate films that show them as they are – and get angry on the mirror, not on themselves. I think that art is worth as long as it speaks rather about those things that people prefer not to speak about – but which are truthful even if uncomfortable.

There is a lot of conformism in the world of art today, even in film, and the limit of the political correctness (otherwise well intended) is that it has seldom changed what people think – but rather what people say. If we wish to change also what they think we need to start by listening to them – like really listening – as a dialogue starts just when you are not certain from the beginning that you are right and the other one is wrong.

That assembly scene also speaks about the limits of democracy and about its ending – the way we knew it. If you don’t invest firstly in educating people, the decisions of the majority might not feel ethical at all. For people in smaller traditional communities is hard to identify these diffuse distant ‘authorities’ who decided for them how the world should change – and they don’t understand why they have to conform and change – even if as the majority of their community prefers living in their tradition.

Your film, read at different levels, talks to us, through the main characters and the choir of protest around them, of the bad and good of which we are made of, of the light and darkness towards which we can go to. Of the good and bad things that are first of all inside of us and outside of us. What do you think of this reading?

One of my aims is to try to preserve in film the complexity and ambiguity of the real world – and not to simplify or to over-interpret it by too much verbal clarification. Yes, we are made of contradictory impulses and traits, we are sometimes rational but more often irrational, our judgements are not so much based on logic but of emotions and circumstances, we are rather selfish than generous, and we cannot escape our loneliness despite our striving for affection. Our subconscious engulfs us like a dark forest, hosting a great number of murky indistinct animalic impulses. Towards the end of the film, Matthias has this revelation that the source of the evil he feels floating in the air – determining him to start checking on his beloved ones – might not come as much from the outer world but rather from himself as the most difficult animal to tame is the one inside you.

The whole film is pervaded by the presence of bears around the village. Real or metaphorical they are wild animals representing, as well as themselves, certain aspects of the human nature. Matthias, at the end of the film, shoots a bear that seems artificial: a sort of a mask under which a man seems to be hiding. Soon after having shot him, in the shadows there seem to emerge many more. Can this be another metaphor of the film? Could it be, that of the protagonist Matthias, the desire to fight against that wild human nature alien to empathy and love?

Matthias first shoots a bear – and for a second, he believes he solved the problem – but instants later, from the darkness seem to appear other creatures whose nature is more diffuse – are they animals, are they human or are they embodiments of his own fears (as one spectator told me) – is for every other spectator to decide.