Watch

Hope and the rebirth of a community in a remote corner of England

‘The Old Oak’, the latest film by director Ken Loach, simple yet powerful, raises many profound issues: work, migrants, the importance of encounter, mutual exchange and coming together to form a strong community. Presented at the Cannes Film.

Out of the suffering of a broken man, TJ Ballantyne, a spark is rekindled to begin a new life; he has almost lost the will to live; once, as he witnessed the breakdown of his local mining community in the north of England, after a long battle with Mrs Thatcher; the second time, when he loses his wife, having left her to suffer, lost in his own depression; the third time, when the pain becomes so unbearable that he thinks of ending his life, but is saved by fate, or perhaps something greater than fate.

On that day, Tj’s life is reborn, or rather, he manages to keep breathing, when a small dog befriends him in his darkest moment. The dog is called Marra, which amongst mining people means ‘companion’, more than a friend, someone who watches out for you and can save your life. The little creature gives him a reason to get up each morning, in the struggling community which has had the heart ripped out of it.

TJ is landlord of the local pub – it is here that he spends his time; surrounded by the black and white photos of the miners when they were strong and united, now with just a handful of sullen customers, angry at the closure of the pits which were their livelihood, forcing them into poverty, not only economically. However, unlike pure racists, they are less harmful, ignorant and struggling, but still capable of doing good.

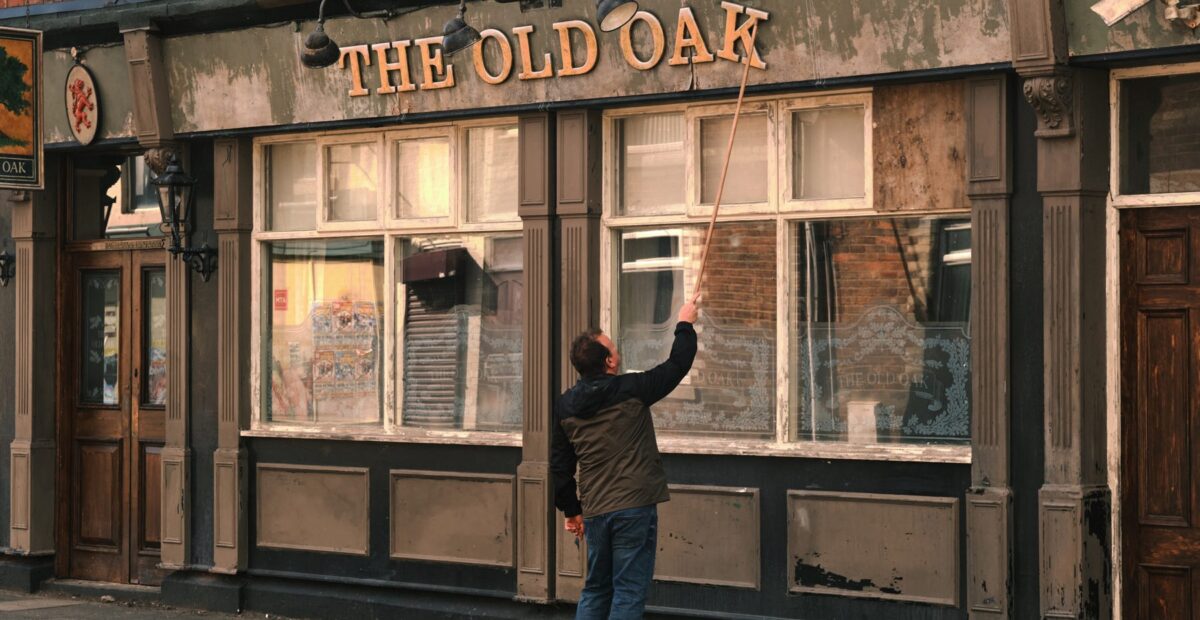

The Old Oak, which is also title of the film, is the name of the local pub, but like its owner, it has become run down. Yet, TJ is like the strong oak tree, that has withstood storms and cold, hard seasons, and remains standing, as firmly planted as life itself, until one day, in our troubled times of wars and displacement of peoples, it offers an opportunity for rebirth.

This opportunity comes in the form of Yara: a young Syrian woman who, together with others, arrives with nothing, in this run downtown, having fled bombardments, violence and death. She has learned English whilst helping the foreign aid-workers in her war-torn country, and she has a passion and talent for photography. In that cold corner of Europe, near Newcastle, she is with her family, numerous and vulnerable, but not her father; he may have been killed or held prisoner in a cruel Syrian prison.

TJ sees something in this young woman in need. He intuits that out of the individual and collective suffering of those who are displaced, a community could be rebuilt. His own life, too, can be rebuilt, healing the mistakes of his despair. TJ does not say much, but when Yara’s camera is damaged by one of his customers who wastes all his money on drinking, he goes out of his way to have it repaired.

He uses his van to deliver essential supplies to the Syrian refugees scattered throughout the town and re-opens the back room of his pub which had been closed since the days when the mining community used to meet together, not only to eat, but for mutual support. TJ reopens the doors so that the locals and the newcomers can share meals together.

Upon the urban arid ground of History, the fertile seed of encounter germinates; human nature is renewed though dialogue and sharing and from the hope, of which Yara speaks so movingly, towards the end of the film, within the setting of an ancient, beautiful cathedral.

Even so, weeds appear, amidst the metaphorical wheat; the insidious weeds of envy, fear, exhaustion and shut down, which threaten to destroy, or try to destroy, the revival of the harmony which once existed.

The film ends on a note of suspense, for suffering does not go away, but that does not necessarily mean defeat, as the 87-year-old director Ken Loach, seems to tell us, arm-in-arm with his faithful screenwriter, Paul Laverty. This is the message of the film, plain and stark, yet sensitively portrayed; simple in content, but powerfully complex; harmoniously weaving together controversial issues, such as ordinary workers, exploited and forgotten; migrants with nothing; the importance of encountering one another, sharing common wounds, which can be healed through finding a new unity together. Just as solidarity depends upon treating one another as equals and building relationships of mutual support.

The Old Oak is full of hope, emanated in the young Yara and the mature TJ. It permeates the film, but it is not alone; it has to live alongside fragile human nature which tends to “blame those who are less fortunate than we are”, as TJ says to an old school friend, whose father was a miner, just like his own father. Victim of the same sad destiny, he betrays and boycotts TJ but in one of the final moments of the film, he reappears, this time in the place where the new community has come together in a moment of shared suffering.

So perhaps even he, once the long list of credits has ended, may yet find within himself, the immense joy of building a new life.